There are three methods by which geographical knowledge is conveyed in digital form.

The first (and usually best) method is via a set of "round-Earth" coordinates of point, line and area abstractions of objects defining their whereabouts on or near the Earth's ellipsoidal (or at least spherical) surface. Geographic information in this form can be processed with a computer to yield acurate quantitative analysis and can subsequently be cast into any number of flat-panel or paper displays for presentation to human eyes.

A second (and second best) method is via a set of "flat Earth" coordinates for the same surface object abstractionss, but having already fictitiously located them on a flat-Earth, using any one of many different planar projections. Geographic information of this type permits less accurate quantitative analysis and has obvious limitations at the edges of the projection.

Digital maps based on either of the foregoing methods are referred to as "vector" maps.

The least desirable method for the conveyance of geographical information is via digital images from the start. Very little analysis is possible, and about all that can be reasonably done with them is to use a computer to present images (or parts of them) for viewing by human eyes, possibly with the addition of some application-specific content.

Why then would it be worthwhile to consider a file format suited specifically to "image" maps? Primarily, because digital map images can easily be obtained by scanning existing paper maps.

While there is an ever-increasing availability of high-quality vector geography, there are many instances where vector data either isn't available or can be obtained only at prohibitive cost. However, a paper map often may be obtained and scanned inexpensively. And even though it is only an image, a scanned map may contain information not readily available in vector form.

There are other sources of digital map images. Sometimes images photographed from flying or orbiting platforms may be distributed in raw form without ever having undergone the typically labor-intensive photogrammetric and interpretive processes which are used by cartographers to turn aerial photographs or satellite images into paper maps.

Regardless of image source, the ability to associate each pixel of a map image with actual ground coordinates will usually exist. Knowledge of this association enables many practical computer applications such as GPS navigation. We propose that such applications can benefit greatly from use of the cross-platform file format and C library components presented here.

So for the remainder of this article, when we talk about computer maps we are referring to the third type, namely image maps.

Maps are a peculiar sub-species of computer image for the following two main reasons:

To be useful for the storage of map images, a graphical file format should be:

We offer developers the two essential ingredients for an effective map image management and access system: an efficient cross-platform file format specification and a library of C source code to perform the necessary geometric and indexing computations. With these two elements (and some rudimentary application code, as offered here), it should be easy to jump-start an application project that makes use of scanned maps or other geographic imagery.

In addition to these two software components, it is assumed that two other widely available software components will be used: zlib compression (for .png-like images) and JPEG library compression (for .jpeg images).

We expect that this technology will be used primarily for maps of relatively large scale (1:25k-1:250k), maps that cover reasonably large local, possibly regional, but not continental areas, and that do not extend into very high latitudes (60+ degrees).

The file format is described here only in general terms: the details are specified in the tileset.h header file. We will describe in some detail a basic form of the file: one that has only a single image layer of 24 bits per pixel (bpp) color, compressed using the lossless zlib compression.

The file is a binary replication of C language structures. It consists of three main blocks of information:

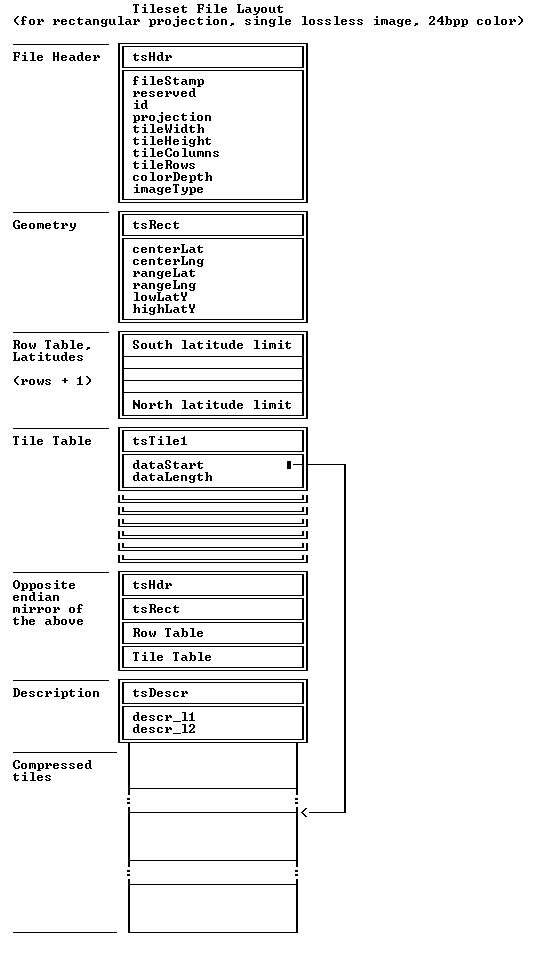

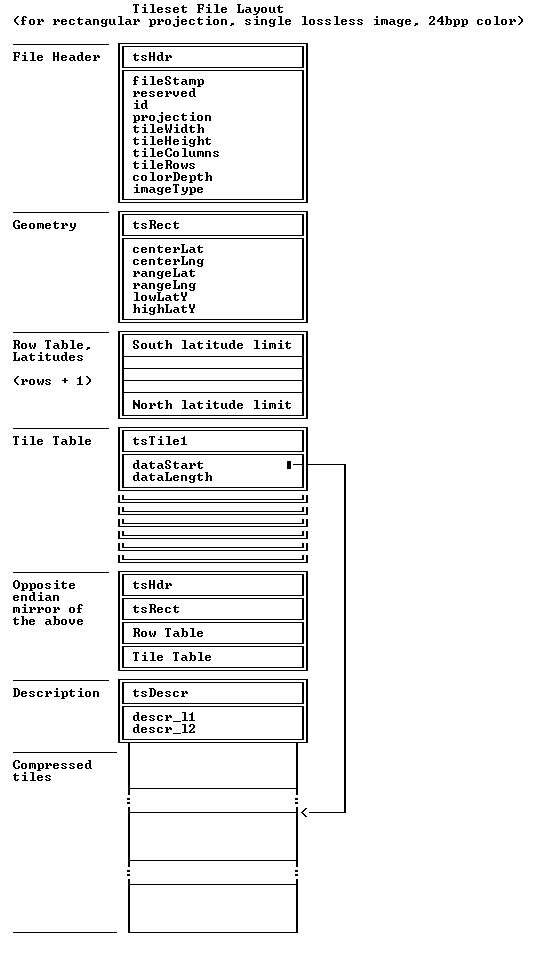

Fig. 1: Tileset File Layout (for rectangular projection, single lossless image, 24-bpp color).

The header provides basic information about the file: the size of each tile, the tile rows and columns count, etc.

Next to the file header is a structure that defines how the tiles and pixels are related to geographic locations. At present, only one such structure - describing the "rectangular tileset projection" - is provided. Of note is that all but one longitude in the file are relative to the tileset mid-longitude value specified therein. This significantly reduces the number of instances in the code where the cyclic nature of the longitude domain must be taken into account.

Following the geometry defining structure, there is an array of latitude values that specify the latitude at each tile boundary, starting at the South boundary of the outhernmost row of tiles, and progressing North, ending with the latitude of the North boundary of the northernmost row of tiles.

Next in the file is an index table providing a file-relative pointer to each compressed tile and its size.

All of the structures and tables listed above contain only two types of data: single-byte characters and 4-byte integers. In order to make it possible to process the file as a read-only file in memory-mapped mode, and to avoid reading complete header structures and tables into memory and possibly having to reverse the byte order in the integers, the foregoing is repeated again in its opposite-endian form. (It makes no difference which endian version occurs first and which second.) In comparison with the tile storage itself this overhead is insignificant.

zlib is used to compress and decompress the tiles with 24bpp pixels. As mentioned in the introduction, the file design provides for "two-layer" maps: background compressed with lossy jpglib compression, and linework and lettering in a png-like layer with transparency. Again, the details can be found in tileset.h

As mentioned in the introduction, one of the TileShare design principles assumes that large tilesets will exist as disk files and that only a small number of tiles - presumably those that are currently visible on the screen or in the window - will be brought into the main memory as needed. Depending on the type of the external storage used, access can be considerably faster if the tiles that are close to each other geogaphically are close to each other in the file. Since tiles cover a two-dimensional (latitude/longitude) domain and the file is essentially a one-dimensional object, this is possible only to a limited extent. Out of many different arrangements, the Morton Order - modified so that rectangular arrangements with different x and y tile counts are accommodated - is used in tilesets. The details can be found in the extensive commentary of the ts_Morton() function in tileset.c. The function is provided for use in programs that compose tilesets, and will not, as a rule, be required by the programs that use tilesets once they have been created.

Tilesets use only two data types: 8-bit bytes and 4-byte integers. The angular measure of latitudes and longitudes are therefore mapped from/to their canonical forms which are signed real numbers in radian measure into 4-byte signed integers using two macros in tileset.h: TS_I4OfAng() and TS_AngOfI4(). The ground resolution of geographic coordinates in the integer representation is in the order of a centimeter: more than sufficient even for tilesets on the high-end of the anticipated scale range.

All tiles in a tileset are rectangular, having identical pixel dimensions, and the same longitudinal "width". This means that a tile width measured on the ground changes continuously not only from one tile row to another, but also from one east-west line of pixels within the tile to the next. In order to preserve the similarity of object shapes between the map and the ground, the design therefore calls for the tile mid-latitude width-to-height aspect ratio on the ground to be the same as the equivalent aspect ratio on the map image. The tile width in pixels must be a multiple of eight, while height is open. The application choice will depend on the scope of the application and the the anticipated use of the tileset. An example implementation might use 128 pixels in latitude (height) by 256 pixels in longitude (width). Note that all tiles in any one east-west row have the same north-south extent on the ground.

This arrangement results in a different latitude extent for each row of tiles; so that each pixel has approximately the same extent on the ground in both east-west and north-south directions. Indeed, as the tiles are getting smaller, the geometry of the planar tileset pixel xy system and geographic coordinates becomes more and more similar to the Mercator projection (which is itself a rigorous mathematical expression of such an arrangement with infinitesimally small tiles). It is therefore reasonable to call this mapping a "discrete" (as opposed to "continuous") Mercator projection. Inside each tile, the latitudes and longitudes can be assumed to be linearly proportional to the pixel coordinates: if tiles have a relatively low north-south extent on the ground (in the order of several kilometers) and relatively low pixel count in north/south direction (hundreds) the error made by linear interpolation of latitudes will remain sub-pixel. There is no error as a result of linear interpolation of longitudes: these are, by definition, proportional to the x pixel coordinates.

A program that constructs a tileset will require two simple geodetic computations: finding the length of an arc of meridian between two latitudes and the length of an arc of the parallel of latitude between two longitudes. If the scale of the tileset is large and the tiles are small, the simple spherical form - given below in the form of C language statements - will suffice:

meridianArcLength = earthRadius * (latitudeNorth - latitudeSouth); parallelArcLength = earthRadius * cos(latitude) * (longitudeEast - longitudeWest);

The ellipsoidal version of these computations - together with many other geodetic computations - can be found in the Hipparchus Library (see http://www.geodyssey.com).

Developers wishing to create and/or use tileset files in their application

will find two C language files,

tileset.h and

tileset.c

containing the definition of all file structures and the C language source

code for the functions that perform data transformation, geometric

computations and the indexing required to access tiles. The code can be used

as source for a library, or the functions in it may be individually included

in the application source code. Since one of the main advantages of the

TileShare system is its cross-platform capability, the code is intentionally

presented and made available with no dependency on a particular development

environment. Both of these files are provided to application developers free

of charge and free of copyright restriction in the hope that they will enable

the development of robust cross-platform geographical applications.

Attribution of this design to Geodyssey Limited at www.geodyssey.com would be

appreciated.

To help jump-start the development of applications that use tilesets, we have prepared programs for three different platforms: the ubiquitous Win32, the Mac OS X and Windows CE. All three are available in full source form.

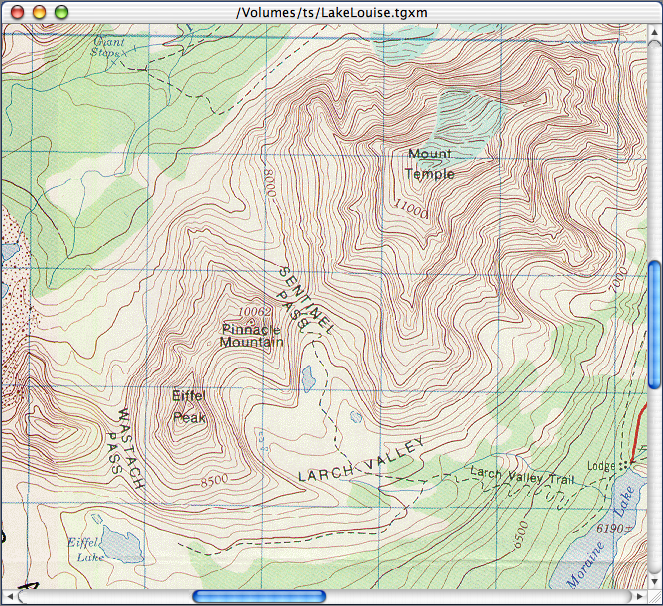

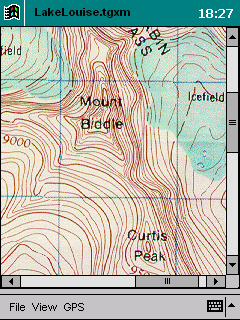

Fig. 2: Tileset Viewers in different environments

All three programs open a read-only cross-platform tileset file in "memory-mapped" mode and use only the most fundamental components of the graphical API of their respective platforms. This is intentional, as the purpose of the code is primarily to be reused in the development of more comprehensive applications.

The viewer for Win32 includes the components required for communication with a GPS device and provides a "moving map" display of the tileset. Unlike most GPS navigation applications which "usurp" the COM port and the device connected through it for their exclusive use, this program consists of two independent executables: a GPS monitor and a tileset display program. Any number of programs that follow a simple data exchange protocol can be executing simultaniously - perhaps multiple viewers displaying different tilesets for the same locale or providing navigational computations and numeric data display.

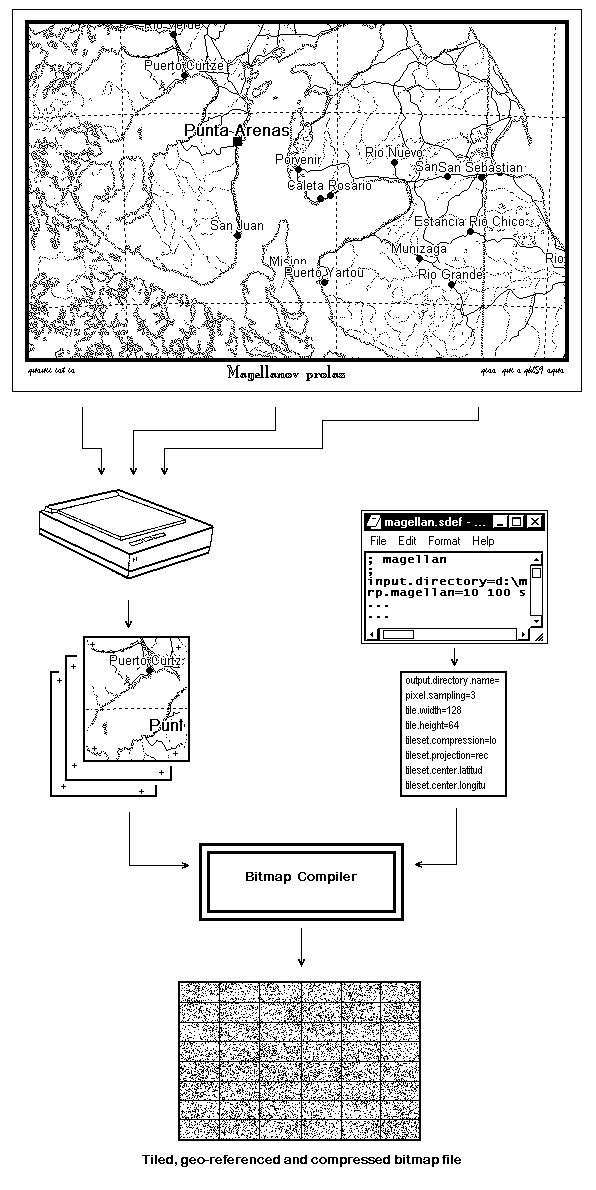

In order to provide end-users with representative scanned map material, and developers to quickly become operational, we have also provided a suite of Win32 programs that comprise a "Tileset Builder's Toolkit". The suite is freely available for download from our web site at http://www.geodyssey.com/tileshare. Figure 3 presents a snapshot of the tilest build process using this toolkit.

Fig. 3: The Tileset Build Process

Yes, you CAN make a silk purse out of a sow's ear!